The Mechanics of Curiosity

In my culture, it's said that names are self fulfilling prophecies. My name Trisha stems from the Sanskrit word “Trishna” meaning thirst and coincidentally, curiosity is my unique selling proposition. If I had to use one word to describe myself, that would be it.

Curiosity has me following utterly unproductive rabbit holes - cultivating hobbies that I’ll abandon in a few months, learning topics that I’ll probably never have use for, or exploring places I’ll never come back to. I sometimes wonder how the “survival of the fittest” mechanism did not weed out people like me from existence.

Turns out, the early man had to be curious to survive. His ability to understand his environment and manipulate it increased the odds of survival. Our most curious ancestors had an advantage over the ones that weren’t. Hence, we’re evolved to leave the beaten track, try out new things and get distracted.

But I have a problem. I leave the track so often that my path resembles a circle now. In 2021, I picked up four new pursuits - hula hooping, learning python, kettlebell training, and blogging. The first three were abandoned on rather quick timelines. The only reason I’ve been able to stick to blogging (somewhat) consistently is because of my attempt to engineer my curiosity.

But first, what is curiosity and how does it work?

Curiosity is a driver that has many benefits like inculcating independent thinking. Much like hunger which motivates us to eat, it motivates us to learn and acquire knowledge. Hunger is aggravated by the smell of food and similarly, a small amount of information acts as a primer which increases curiosity. However, once we consume enough of it, information serves to reduce further inquisitiveness.

I’ve read, talked and thought a lot about curiosity. Through the process, I’ve come to understand that there are two underlying laws that govern how it works.

The first law

Curiosity requires an exploration vs exploitation tradeoff.

There are essentially two types of behavior that we observe among foraging animals:

Exploitative foragers : They tend to stick with their current food patch till the bitter end. They don’t explore and hence, when their current food patch is depleted, their survival is at risk.

Explorative foragers : They frequently leave their current food patch in search of something else. Their survival depends on the odds that they find a food patch before their energy levels are exhausted.

Survival for the foragers depends on making the right tradeoff between exploration and exploitation. Why did I go off on this tangent? Because this behavior is common among humans too. There are explorers (Me!) and exploiters. Leveraging curiosity requires a tradeoff between both modes.

The return on curiosity (R) and curiosity follows an S shaped graph. For example, If I’m writing a book, R would be the number of pages I write. The increase in R is flat at the start as this is the stage that I would ideally spend thinking, researching and creating the base. Post this phase, R would be proportional to my curiosity. However, increase in R is also proportional to the potential for further return. In the beginning, this potential is high because there’s a lot that can be written. But as I get closer to the end, there are fewer topics to write about and R stagnates.

Explorers are perpetually stuck at A and don’t see any significant returns. On the other hand, exploiters stagnate at C and don’t see any incremental returns. The ones who are able to leverage their curiosity are at the tradeoff point B.

The second law

It’s impossible to be curious about what we think we know.

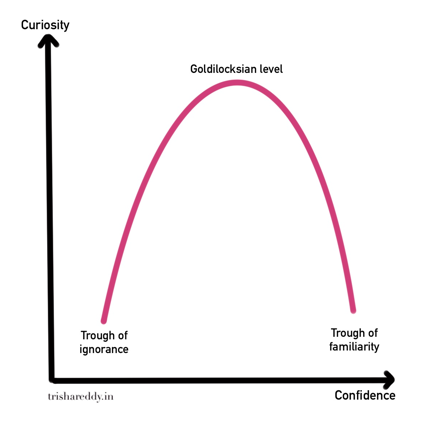

Researchers have discovered a U-shaped relationship between curiosity and confidence in a subject. If you have a really high or really low confidence in something, your curiosity in that subject would be low. The sweet spot seems to be a Goldilocksian level of confidence—not too much nor too little.

Once you’re curious about something, you have to try and avoid the “Trough of Familiarity” at all costs. At this stage, the initial excitement fades, need for novelty kicks in and the new pursuit gets abandoned.

One way to avoid this dangerous zone is to remind ourselves that what we know in this constantly changing world is very very limited. This can be done by cultivating and maintaining a beginner's mind. It not only helps avoid procrastination but also helps avoid anxiety. Both of which reduce the probability of the pursuit being abandoned.

Engineering curiosity

Newton is (in?)famous for wondering why apples fall straight to the ground. This question sent him down a rabbithole that eventually led to physics as we know today. If we study Newton, we can observe how the two laws apply to him.

He explored various interests like the philosopher's stone and deconstruction of the Bible. However, he doubled down on his pursuit of physics and managed to stay relevant for more than three centuries. This is the exploration vs exploitation framework in play.

He’s also famous for saying “What we know is a drop, what we don’t know is an ocean”. Despite spending his entire life in pursuit of science, he knew how truly limited his own understanding was. His genius is the consequence of a beginners mindset.

Curiosity is complex. These two laws only explain it partially. But this framework is interesting because it proposes that curiosity is not some gene that you’re born with. It can be engineered. And if you’re like me, suffering due to too much of it - it can be tamed!